So far, we’ve got software running on the system that allows us to use a console to input and output data. While this is all fine and dandy, our underlying uart device driver used to read from the console does so by polling. This involves the driver code checking if the recieve buffer is not empty every time it wants to read. This scheme is not a very efficient use of system resources - particularly when the system in question supports interrupts.

The whys and hows

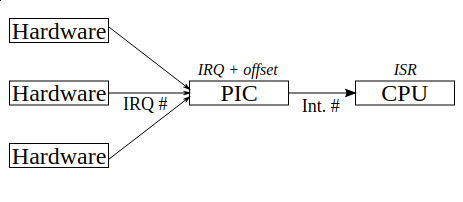

An interrupt is a alert -from the hardware - that needs attention from the software. For instance, when we type anything on the console, the processor is alerted of this event so that it can be handled in a timely manner. This may require the current flow of control/execution to be interrupted - hence the name. Since they can occur at any time, interrupts (at least hardware interrupts) are asynchronous. How the interrupts are handled depends on interrupt handling/exception handling model of the processor.

Let’s go back to chapter 2 where we identified that the first 240 bytes of code represent the interrupt vector table with each entry pointing to an interrupt handler or interrupt service routine - the software fucntion that handles a particular interrupt. The ARM Cortex-M3 and the Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller (NVIC) prioritize and handle all of these interrupts - called exceptions in the Cortex-M3 world. When an exception is triggered, the processor state - represented by it’s registers - is automatically pushed to the stack and restored from the stack once the exception handling is complete - that is when the ISR exits.

The interrupt can be enabled and prioritised using the SFRs of the NVIC. For now, since we’ll be dealing with the interrupt generated when data is receieved by the UART device, we won’t bother with priority. By the way, we have already dealt with exception handling in chapter 2, which is how we setup our data/bss segments and got to main() in the first place. This was done by invoking the handler to the Reset exception - whose address was made available at location 0x00000004. The exception is triggered on power-up or warm-reset. There are 9 other such exceptions and 59 interrupts (IRQs) generated by peripherals. Other than the Reset, Hard Fault and Non-Maskable Interrupt, all other interrupts have programmable priorities.

The details regarding the features of the NVIC are available in section 2.5 of the data sheet.

Interrupt-driven UART

If we look at table 2-9 on the data sheet, we see that vector number 21 refers to UART0 - i.e. an interrupt generated by the peripheral UART0. There can be several conditions which result in an interrupt generated by the UART. As discussed in the beginning, we want to improve the our UART driver - by reading data from the recieve buffer only when it is available - with the use of interrupts.

How do we go about setting up generating, receiving and handling this interrupt?

Since the UART0 is the device that generates the interrupt, our task would be to ensure that the device does so when a certain condition is met, which in our case is on recieving data. This can be done with the aid of some SFRs meant for this purpose. If you look at section 12.3.6, you’ll see that what we need to do to get the UART to generate an interrupt on recieving data are:

- Enable the bit in the

UARTIM(UART Interrupt Mask) register corresponding to the Recieve Interrupt so that it can be routed to the interrupt controller. - Use

UARTRIS(UART Raw Interrupt Status) orUARTMIS(UART Maskes Interrupt Status) register to monitor the status of the interrupts. - Clear the bit corresponding to the Recieve interrupt in the

UARTICR(UART Interrupt Clear) register when we’re done handling the interrupt.

If you’ve noticed the register descriptions, the UARTMIS/UARTRIS and UARTICR look identical, a property we will leverage when finding out what interrupt is triggered and clear it appropriately, once handled.

To this end, we’ll define these registers within our uart_regs structures to reside at teh appropriate offset and perform the above tasks with a set of functions as follows:

/* Enable the said uart interface to generate interrupts

* depending on the flag set - conditions for interrupt generation.

* This interrupt is then sent to the interrupt controller.

*/

static void uart_irq_enable(uint32_t irq_flags)

{

uart0->IM |= irq_flags;

}

/* Clear the interrupt for said uart interface

* depending on the flag set.

*/

static void uart_irq_clear(uint32_t irq_flags)

{

uart0->ICR = irq_flags;

}

/* Get the current interrupt status of the said uart interface

* depending of whether is_masked is true or false, it returns

* the masked or raw interrupt status.

*/

static uint32_t uart_irq_status(bool is_masked)

{

if(is_masked)

return (uart0->MIS);

else

return (uart0->RIS);

}

Notice how these functions are defined generically to set/monitor/clear any of the UART interrupts supported. This allows for our driver to be scaled to accomodate more interrupts should the need arise. Now, enabling the interrupt is done when we init the uart device before we actually turn it on so that any data received at any time from the point of the device being turned on triggers an interrupt.

It’s not enough to have the interrupt generated by the device. This interrupt has to be routed through the interrupt controller to the processor so that the control of execution can then be handed to the interrupt handler/vector/ISR which will be use to process the interrupt. By enabling the recieve interrupt bit in UARTIM, we’ve ensure that an interrupt generated by the device when it recieves data is routed to the interrupt controller. Our next step should be to ensure that the interrupt controller “informs” the processor of this. For this, we’ll need to look at the SFRs of the NVIC (Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller).

A detailed description of the NVIC is available in section 3.1.2. Let’s go to the SFRs and see what we can do to get our UART interrupt through to the processor via NVIC.

Section 3.4 details the register descriptions of the various NVIC registers.

To enable in interrupt, which in the context of the NVICrefers to enabling it to “forward/route” said interrupt to the processor, we’ll need to identify the interrupt number and set the respective bit in one of the EN0 or EN1 (Interrupt Set Enable) registers. From table 2-9, we see that the interrupt number for the UART0 Interrupt is 5 (with a vector number of 21). To enable this interrupt, we set bit number 5 on EN0. The simplest way of doing this is:

void interrupt_set_enable(uint8_t irq_num)

{

uint32_t *pEN0 = (uint32_t*)0xE000E100;

*pEN0 |= (1 << irq_num);

}

But where is the modularity/scalability/readability (aka FUN!) in that?!

What we’ll do is create a pair of files which will hold all of the data structres, methods, definitions, macros for managing the NVIC subsystem, similar to what we did with the UART. In this, our representation of the various NVIC SFRs looks like:

/* NVIC register map structure.

* Refer: http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf Table 3-7.

* Note: all offsets in comments are from NVIC_BASE == 0xE000E100

*/

typedef struct __attribute__ ((packed)){

uint32_t EN0; // 0x00 Interrupt 0-31 Set Enable

uint32_t EN1; // 0x04 Interrupt 32-43 Set Enable

uint32_t reserved[30]; // 0x08-080 reserved

uint32_t DIS0; // 0x80 Interrupt 0-31 Set Disable

uint32_t DIS1; // 0x84 Interrupt 0-31 Set Disable

}nvic_regs;

static volatile nvic_regs *nvic = (nvic_regs*)NVIC_BASE;

We can then define functions to enable/disable interrupts based on thier vector numbers. These vector numbers are tabulated as a set of macros in nvic.h as defined in tables 2-8 and 2-9.

/* Enables the interrupt specified via

* param vector_num.

* See: http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf Section 3.4 (Page 109)

*/

void nvic_irq_enable(uint32_t vector_num)

{

/* Interrupts 0-31 enabled via EN0 */

if(vector_num >= IRQ_GPIOA && vector_num <= IRQ_ADC0_SEQ1)

{

nvic->EN0 |= (1 << (vector_num - IRQ_GPIOA));

}

/* Interrupts 31-43 enabled via EN1 */

else if(vector_num >= IRQ_ADC0_SEQ2 && vector_num <= IRQ_HIBERNATE)

{

nvic->EN1 |= (1 << (vector_num - IRQ_ADC0_SEQ2));

}

}

/* Disables the interrupt specified via

* param vector_num.

* See: http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf Section 3.4 (Page 109)

*/

void nvic_irq_disable(uint32_t vector_num)

{

/* Interrupts 0-31 disabled via DIS0 */

if(vector_num >= IRQ_GPIOA && vector_num <= IRQ_ADC0_SEQ1)

{

nvic->DIS0 |= (1 << (vector_num - IRQ_GPIOA));

}

/* Interrupts 31-43 disabled via DIS1 */

else if(vector_num >= IRQ_ADC0_SEQ2 && vector_num <= IRQ_HIBERNATE)

{

nvic->DIS1 |= (1 << (vector_num - IRQ_ADC0_SEQ2));

}

}

Notice how in both enable and disable functions, we derive the interrupt number by subtracting the vector number of the first interrupt for that register (IRQ_GPIOA/IRQ_ADC0_SEQ2) from the vector number of the inetrrupt of interest.

The final step is to define a handler for this interrupt, where we process the interrupt. Remember our vector table from Chapter 2 where we defined the first 15 execptions. Let’s expand that table to include the remaining interrupts supported by our hardware - as seen in table 2-9. We can go ahead and define the unused interrupts (so far), like we did the unused execptions - via a call to the hang function. Let’s then place uart0_irq_handler in the vector table at the location corresponding to it’s vector number.

We’ll define this function in uart_drv.c since it involves handling a uart interrupt. Let’s also provide a symbol for reference in our startup file (where lies the vector table) - to keep the linker happy. What do we do in terms of handling? For starters, let’s try and print some text everytime the interrupt is triggered - which should be everytime our UART/serial device recieves data. If you recall, QEMU redirects all console inputs/outputs to the serial device - which means, anytime we type something in the QEMU console, we should have our UART recieving data and the interrupt being triggered. Our simplest interrupt handler will look like this.

void uart0_irq_handler(void)

{

uint32_t irq_status;

char *msg = "!!!UART0 Interrupt!!!";

irq_status = uart_irq_status(true);

uart_irq_clear(irq_status);

while(*msg)

{

uart_tx_byte(*msg);

msg++;

}

}

Let’s put this to the test shall we?

This is what we see on the console when we run our image and type any character

$ qemu-system-arm -M lm3s6965evb -kernel startup.bin -nographic -monitor telnet:127.0.0.1:1234,server,nowait

Hello, World

...

Go on, say something...

!!!UART0 Interrupt!!!

telling us that the interrupt is genearted by UART0 when it receives data and this interrupt is routed to the processor by the NVIC. The processor then transfers control to the interrupt handler present in the vector table according to the vector number of the interrupt.

Now, onto our main objective - replace the polling scheme used to read data recieved by the uart with an interrupt driven scheme of doing the same. The interrupt indicates that a byte of data has been received by the uart, which means we can read the byte received on every occurence of the interrupt - represented by none other than the interrupt handler. We can have a char variable into which we read the received byte and then write it back to the console. This will give us the ability to display what we type on the console - yes, the same thing we take for granted on our computers/cellphones etc.

void uart0_irq_handler(void)

{

uint32_t irq_status;

char c;

irq_status = uart_irq_status(true);

uart_irq_clear(irq_status);

if(irq_status & UART_RX_IRQ)

{

c = uart0->DR & UARTDR_DATA_MASK;

if(c == '\r')

{

uart_tx_byte('\n');

}

else

{

uart_tx_byte(c);

}

}

}

All we’ve added is a check to see if the triggered interrupt is the UART RX interrupt and then copy the first 8-bits of the UARTDR into the placeholder char variable. If it represents a carriage return, we transmit a next line \n, otherwise we simply transmit the character. A more thourough handler would handle non-printable control characters like backspace, delete, the up/down/left/right arrows etc. This can be your assignment, perhaps!

Before we proceed, let’s add nvic_irq_enable(IRQ_UART0) in our main() function to enable the UART0 interrupt. Since we’re on the subject of interrupts, it is wise to keep all interrupts disabled during initialization and enable them at the end of our initialization routine - main() in this case. This disable/enable can be achieved by changing the processor state to disable/enabel all inetrrupts - using the cps instruction - refer. Let’s define these in a header file and then stick them in main().

/* To enable all interrupts with programmable priority.

* Refer: Refer http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf

* Table 2-13 and Section 2-3-4

*/

static inline void irq_master_enable(void)

{

/* https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/Extended-Asm.html

* asm statements that have no output operands, including asm goto statements,

* are implicitly volatile.asm statements that have no output operands,

* including asm goto statements, are implicitly volatile.

* Included the __volatile__ qualifier anyway to put in this note.

*/

__asm__ __volatile__ ("cpsie i");

}

/* To disable all interrupts with programmable priority.

* Refer: Refer http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf

* Table 2-13 and Section 2-3-4

*/

static inline void irq_master_disable(void)

{

__asm__ __volatile__ ("cpsid i");

}

Notice how we’re only disabling and enabling interrupts and not execptions. We can disable/enable all exeptions too, using the cpsid f and cpsie f instructions (except teh NMI which cnanot be disabled). It is not recommended because these exceptions represent system faults that we will need to handle/debug (although presently, we only hang if these are ever encountered).

Now, if you try this (build and run) and type on the qemu console, you will see what you type - something you couldn’t do before!

Have you noticed how in the last couple of chapters, we’ve derived the baud-rate based on an assumption that the system clock on board operates at 12 MHz? Where did we get this from? How are we so certain? And can we change this at all?

In the next chapter, we’ll explore how to work with our crystals, oscillators and clocks in the all important endeavour of measuring time.

References

As I’ve stated earlier, the datasheet for LM3S6965 is a good starting point and reference to understand interrupts and NVIC in particular.

This article by Chris Coleman provides a detailed explanation of the NVIC with examples dealing with the more advanced concepts in interrupt/exception handling that we haven’t dealt with here.

The ARMv7-M Architecture Reference Manual of course is the go to reference nto only for NVIC but for the ARMv7-M microcontrollers in general.