Now, that you have your setup ready, let’s get coding. Remember, this is a bare-metal system - it has no software on-board and you have to do everything.

Wading through assembly code

We know that the hardware includes an ARM Cortex-M3 microcontroller, so we should be able to use ARM assembly instructions to get something done for us, say, find the sum of two numbers. That sounds like a good starting point.

.syntax unified

.thumb

tos: .word 0x5000 /* initial value of stack pointer r13 */

reset: .word start /* initial value of program counter r15. STart of execution */

.text

.thumb_func

start:

ldr r0, =num1 /* r0 == &num1 */

ldr r1, [r0] /* r1 == num2 */

ldr r0, =num2 /* r0 == &num2 */

ldr r2, [r0] /* r2 == num2 */

add r3, r2, r1 /* r3 == r1 + r2 */

stop:

b stop

num1: .word 5 /* first number */

num2: .word 6 /* second number */

Let’s save this file as hello.s as we’ll build upon this file as we journey towards a Hello, World program.

You can see how we use the load instruction to load numbers into the cpu registers, add them and save the result into another cpu register:

ldr r0, =num1 /* r0 == &num1 */

ldr r1, [r0] /* r1 == num1 */

ldr r0, =num2 /* r0 == &num2 */

ldr r2, [r0] /* r2 == num2 */

add r3, r2, r1 /* r3 == r1 + r2 */

There are a few other things in our assembly code that need a bit of context.

At the very beginning, you see .syntax unified and .thumb which are what we call assembly directives. These are “psuedo-opcodes” that direct the assembler to perform operations other than assembly. Assembly involves the assembler operating on the instruction opcodes such as ldr and add ,in our case, to produce executable machine code (binary representations of these instructions that can be executed by the processor).

Coming back to assembly directives, .syntax unified is used to take advantage of a unified syntax for the ARM instruction set. The ARM processor family supports the ARM, Thumb and Thumb-2 instruction sets - depending on the architecture. By using .syntax unified, we are instructing the assembler to read the code that follows as if it were written in Unified Assembler Language UAL. Long story hort, assembly code wrtten in UAL can be assembled into ARM or Thumb instructions - there is no need to write the assembly separately for each instruction set.

Now, it follows that .thumb directive instructs the assembler to assemble the code that follows into Thumb instructions.

.text marks the beginning of the code/text section, which is where, as you know, resides the code and constants (within the executable). .thumb_func directive informs the assembler that the function that follows is to be assembled as thumb - I know this sounds superfluous given we’ve used .thumb to say the same about all of the code in the file. However, I have seen assemblers generate ARM instructions if this is not explicitly included at the head of every function label within an assembly file.

Now, coming to labels, you can see start, stop, num1, num2 which are used to refer to a location of the instruction within memory. They are used as sort of a readable representation of a memory address. For instance, start represents the memory address where the instruction ldr r0, =num1 is located in memory. The labels num1 and num2 represent the memory address where the .word(s) 5 and 6 are stored. The .word directs the assembler to reserve space in memory to hold the value that follows it. Before we move on, notice how at the label stop, we have b stop - which is an infinite loop so the program hangs until we turn-off/reset the microprocessor. To find the addresses associalted with the labels littered around in the file, use:

arm-none-eabi-nm part_1.elf

00010028 T __bss_end__

00010028 T _bss_end__

00010028 T __bss_start

00010028 T __bss_start__

00010028 T __data_start

00010028 T _edata

00010028 T _end

00010028 T __end__

00000018 t num1

0000001c t num2

00000004 t reset

00080000 N _stack

00000008 t start

00000016 t stop

00000020 t sum

00000000 t tos

There are a couple of labels that we haven’t talked about yet, tos and reset. The ARM Cortex-M3 processor, when reset reads two words from memory at:

- Address

0x00000000: into the stack pointer register - r13 - Address

0x00000004: reset vector (which is copied into the program counter register r15) from where execution begins.

These lables are mark the first two words - with tos tentatively set to 0x5000 representing the top of stack (hence tos) and the reset vector pointing to start which is where our code begins (and consequently so will the execution of our code). This constitutes what we call the interrupt vector table or vector table. More on this later.

Assembly and Linking

Let’s assemble this file and then link it to generate an executable - elf.

arm-none-eabi-as -g -mcpu=cortex-m3 -o hello.o hello.s

-g - generates debug information.

-mcpu - assembles code for a given cpu - in this case, cortex-m3.

arm-none-eabi-ld -Ttext=0x0 -o hello.elf hello.o

-Ttext - specifies the start address of the text segment. We need to keep it at 0x0 because because Cortex-M3 at startup begins by reading from address 0x0.

You’ll see the linker here arm-none-eabi-ld complain:

arm-none-eabi-ld: warning: cannot find entry symbol _start; defaulting to 0000000000000000

because it expects a _start symbol/label from where execution begins. We’ll eventually use _start to lable the start of execution.

The executable generated is in the ELF (executable and linkable format) - one that can be loaded and excuted in a Linux or Unix-like environment. However, we’re dealing with a bare-metal system with no operating system running whatsoever. This would require us to use a raw binary dump of the elf executable which can be run on our system:

arm-none-eabi-objcopy -O binary hello.elf hello.bin

-O - generate output of specified format - in this case, binary.

If you notice the output files generated so far - part_1.o, part_1.elf, part_1.bin - the .o and .elf files span between a few hundred to a few kilobytes - owing to their elf format (headers, footers etc.) whereas the .bin file is about 28 bytes representing the actual amount of code necessary to add two numbers and save the result in a register on a cortex-M3 cpu. To run this on our bare-metal system (as simulated by qemu):

qemu5.1-system-arm -M lm3s6965evb -kernel hello.bin -nographic -monitor telnet:127.0.0.1:7777,server,nowait

-M - specifies the simulated machine on which to run the binary - in this case, lm3s6965 board.

-kernel - the “kernel” or “executable” to run - in binary format.

-nographic - run as a command-line application output everthing on terminal. The serial port is also re-directed to terminal.

-monitor - set-up the QEMU monitor interface to examine the simulated machine running your binary. In this case, it is set up on localhost(127.0.0.1) and port 7777. server, nowait referes to QEMU setting up a telnet server but not waiting on a connection to run the executable.

In another terminal window:

telnet localhost 1234

to connect to the telnet server hosted by the qemu machine, you’ll see:

$ telnet localhost 1234

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to localhost.

Escape character is '^]'.

QEMU 5.1.0 monitor - type 'help' for more information

(qemu)

Now, to see if our program has run successfully, try examining the registers on the simulated machine:

(qemu) info registers

R00=0001002c R01=00000005 R02=00000006 R03=0000000b

R04=00010030 R05=00000000 R06=00000000 R07=00000000

R08=00000000 R09=00000000 R10=00000000 R11=00000000

R12=00000000 R13=00005000 R14=ffffffff R15=00000018

XPSR=41000000 -Z-- T priv-thread

FPSCR: 00000000

Notice how R01=00000005 R02=00000006 have our inputs and the result is stored in R03=0000000b (0x0b == 11) - our program works!

Take a look at R13=00005000 R15=00000012 - we’ve seen earlier that R13 represents the stack pointer and R15, the program counter. The value stored in stack pointer is the value at address 0x00000000 labelled tos. The program counter points to the label stop as we have set up a loop forever by branching to stop.

Earlier, we mentioned that on reset, the value at address 0x00000000 is copied onto the stack pointer R13 and the value at address 0x00000004 is copied onto the program counter R15 which is where execution will begin. We’ve seen the first statement in action. To see how execution begins at the address copied from 0x00000004, run the binary on QEMU but halt execution:

qemu-system-arm -s -S -M lm3s6965evb -kernel hello.bin -gdb tcp::5678 -nographic -serial /dev/null

-S - freeze (or stop) execution at startup.

-s - used instead of -gdb tcp::1234 or running gdbserver in the qemu prompt.

-serial - redirect serial output to a char device - in this case /dev/null.

-gdb - sets up the gdbserver on the localhost (IP: 127.0.0.1) on tcp::5678 - tcp port 5678

open up another terminal and run:

arm-none-eabi-gdb hello.elf

connect to the gdbserver on localhost:5678

(gdb)target remote localhost:5678

Remote debugging using localhost:5678

start () at hello.s:10

10 ldr r0, num1

(gdb) info registers

r0 0x0 0

r1 0x0 0

r2 0x0 0

r3 0x0 0

r4 0x0 0

r5 0x0 0

r6 0x0 0

r7 0x0 0

r8 0x0 0

r9 0x0 0

r10 0x0 0

r11 0x0 0

r12 0x0 0

sp 0x5000 0x5000

lr 0xffffffff -1

pc 0x8 0x8 <start>

xpsr 0x41000000 1090519040

see how execution has stopped excatly at startup represented by label start which is also the value in the program counter R15. You may say, how convenient that start of execution in my example is where I begin any assembly instruction at all. Well, if you don’t believe me, move start to any other address or even change the reset label to point to another address and try examining the results via the debugger!

We can go on to do much more with assembly instructions this way, say array/string manipulation, searchig, sorting etc. We can even program the system to write to and read from peripherals, respond to interrupts, set up timers and so on. But doing so in assembly language is rather tedious and here’s where higher level programming langauge such as C comes into the picture.

Getting our C legs:

What do we need to have running on our system to be able to execute a program whose source is in C?

This is what’s normally referred to as the C runtime environment. In fact, in a lot of source code for embedded systems, you may have come across files named crt0.s or crt0.c - which represents this environment/setup programmed for the particular hardware in assembly or even C (take that chicken and egg!). This runtime configures the hardware appropriately to be able to run the program generated by a C compiler.

In order to execute a program written in C, our system needs to have the following capabilities:

- maintain a region of memory to hold variables with global scope that are initialized - (extern and static in C) - where they can be read/modified - data segment

- maintain a region of memory to hold variables with local scope (restricted to the function/block in which they are defined) - where they can be read/modified. stack

- manage storing/retrieving arguments to functions as well as the return address of the function. - stack

- clear the memory region to hold uninitialized variables with global scope. bss segment

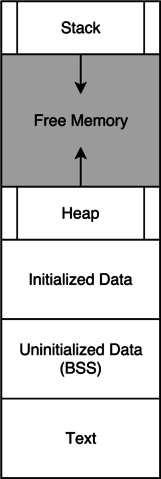

You remember these “segments” being referenced in your last interview, don’t you? Arranged like this?

This figure above raises the question - where in the memory do these segments reside and how do we instruct the hardware to manage these? For this, we’ll need a copy of the data sheet for the hardware of choice, LM3S6965 (here) and a linker script.

If we look at the memory map in Table 2-4, addresses in the range 0x00000000 to 0x0003FFFF (256kB) represent the on-chip flash (non-volatile memory) and 0x20000000 to 0x2000FFFF of on-chip SRAM (volatile memory). Since code doesn’t have to change at runtime, the text segment can continue residing in the on-chip flash i.e. the code doesn’t have to be relocated to any other memory region (although we could if we wanted to).

The data and bss segments however, will have to be relocated to the volatile memory - these hold variables with global scope which will be modified routinely. The volatile memory region will also hold the stack - which is where local variables, arguments and return addresses will be present and modified. It is fairly easy to configure where the stack - the address held at memory location 0x00000000 initializes the stack pointer - in the ARM Cortex-M3. The stack as defined by the ARM Architecture Procedure Call Standard AAPCS is full-descending, i.e. the it “grows” downwards in memory. Let’s then set the initial value of the stack pointer to the highest address in the volatile memory space 0x2000FFFF. You may be wondering what if the stack continues to grow and overwrite the data and bss segments that are also in the volatile memory space? Yes, it is possible and there are ways to detect this. We’ll discuss that later.

Now that we know where each section of the program will reside, we’ll need a way to ensure that this is set up before we can run any C program (executable) on our system. How do we get these various sections to be placed where we want them? That’s where the linker script comes in. Recall how we linked our object file to get an executable .elf file, where we specified the start address of the text segment. The linker, arm-none-eabi-ld can also accept a linker script written in a specialized scripting language specific to the ld application. This script can be used to specify memory regions corresponding to various segments in accordance with the memory map - which the linker understands and complies with.

Let’s change hello.s a bit and save the result of the sum of two numbers in memory. We’ll need a global variable to hold this result and the space for this can be reserved using the .space assembler directive.

.syntax unified

.thumb

tos: .word 0x5000 /* initial value of stack pointer r13 */

reset: .word start /* initial value of program counter r15. Start of execution */

.text

.thumb_func

start:

ldr r0, =num1 /* r0 == &num1 */

ldr r1, [r0] /* r1 == num1 */

ldr r0, =num2 /* r0 == &num2 */

ldr r2, [r0] /* r2 == num2 */

add r3, r2, r1 /* r3 == r1 + r2 */

ldr r4, =sum /* r4 == &sum */

str r3, [r4] /* sum == r3 */

stop:

b stop

.data

num1: .word 5 /* first number */

num2: .word 6 /* second number */

sum: .space 4 /* 4-byte space in memory for the result */

Notice how sum is used to reserve space for a 4 byte value and how the result is is stored into sum. Try building this and running the binary on qemu as shown earlier. Also, we’ve labelled the block with the variables .data, to indicate that these belong in the data section. Although you will see the sum being held in r2 the value at label sum will be zero - that is, the result was never stored here. Why is this, you ask? Because addresses in the range 0x00000000 to 0x0003FFFF the on-chip flash which serves as read-only memory (although it can be written to, but not quite like writing to RAM) and sum happens to be in this address range. We want sum or any other variable of global scope to be located in the on-chip SRAM 0x20000000 to 0x2000FFFF where they can be read/modified at will. How do we do this? With the linker script of course:

MEMORY

{

FLASH (rx) : ORIGIN = 0x00000000, LENGTH = 256K

SRAM (rw) : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 64K

}

SECTIONS

{

. = 0x00000000;

.text : {

hello.o (.text)

. = ALIGN(4);

} > FLASH

.data : {

_sram_sdata = .;

hello.o (.data)

. = ALIGN(4);

_sram_edata = .;

} > SRAM AT > FLASH

_flash_sdata = LOADADDR(.data);

_sram_stacktop = ORIGIN(SRAM) + LENGTH(SRAM);

}

Without going into too much detail, the linker script here, aptly named linker_script.ld, sets up the various sections, thier contents and thier location within memory. MEMORY command describes the location and size of blocks of memory in the target - in accordance with the memory map (as seen in the data sheet). SECTIONS command describes how the various sections are to be placed in memory.

We start the SECTIONS with . = 0x00000000;. . represents the location counter within SECTIONS and is incremented according to what follows - although it is initialized to zero at the start of SECTIONS, we’ve placed it there anyway. Next, .text specifies what goes into the .text section of the executable - in this case, the .text section of hello.o. If we have multiple object files with sections that need to reside in the .text section of the executable, we preceed the (.<section_name>) with a * - which acts as a wildcard.

We see again . being assigned to ALIGN(4), what this does is align the location/address at that position in the linker script to the nearest 4-byte boundary. At the end of .text we see > FLASH which is a means of assigning a section to a previously defined region of memory - in this case FLASH.

Variables can be assigned to . and they hold the address of the location counter at the point where they are initialised - like _sram_edata. What do we make of > SRAM AT > FLASH? The AT command is used to specify the load address of a section - the address where the section is located in the executable. So, the .data will reside in the SRAM region with it’s load address in FLASH. _flash_sdata is initailised with LOADADDR(.data) - which returns the absolute load address of the named section - .data. Since we have the memory regions supported, we can calculate the highest memory address in the on-chip SRAM, which can be used to initialize the stack pointer at the start of the program - _sram_stacktop. These variables are available for us to use in our program. With this in place, here is the new hello.s

.syntax unified

.thumb

tos: .word _sram_stacktop /* initial value of stack pointer r13 */

reset: .word _start /* initial value of program counter r15. Start of execution */

.text

.thumb_func

_start:

/* relocate data section to the SRAM */

ldr r0, =_flash_sdata

ldr r1, =_sram_sdata

ldr r2, =_sram_edata

cmp r2, r1

beq add_nums

data_loop:

ldrb r4, [r0], #1

strb r4, [r1], #1

cmp r2, r1

bne data_loop

add_nums:

ldr r0, =num1 /* r0 == &num1 */

ldr r1, [r0] /* r1 == num1 */

ldr r0, =num2 /* r0 == &num2 */

ldr r2, [r0] /* r2 == num2 */

add r3, r2, r1 /* r3 == r1 + r2 */

ldr r4, =sum /* r4 == &sum */

str r3, [r4] /* sum == r3 */

stop:

b stop

.data

num1: .word 5 /* first number */

num2: .word 6 /* second number */

sum: .space 4 /* 4-byte space in memory for the result */

The stack pointer is initailsed to _sram_stacktop as discussed before. Another notable change is in _start:

/* relocate data section to the SRAM */

ldr r0, =_flash_sdata

ldr r1, =_sram_sdata

ldr r2, =_sram_edata

cmp r2, r1

beq add_nums

data_loop:

ldrb r4, [r0], #1

strb r4, [r1], #1

cmp r2, r1

bne data_loop

What we’re doing here is copying the data section from the executable in the flash - beginning at _flash_sdata to the RAM beginning at _sram_sdata. Following this we add the numbers and save the result in a global variable. Let’s build hello.bin and along the way list the symbols in the elf executable:

arm-none-eabi-nm hello.elf

0000001e t add_nums

00000012 t data_loop

00000048 A _flash_sdata

20000000 d num1

20000004 d num2

00000004 t reset

2000000c D _sram_edata

20000000 D _sram_sdata

20010000 D _sram_stacktop

00000008 t _start

0000002e t stop

20000008 d sum

00000000 t tos

We see how the globals are now located in within the SRAM space 0x00000000 to 0x20000000. Notice how _sram_stacktop is at the highest SRAM address plus one. Now run this binary on our machine and examine the registers and memory:

(qemu) info registers

R00=20000004 R01=00000005 R02=00000006 R03=0000000b

R04=20000008 R05=00000000 R06=00000000 R07=00000000

R08=00000000 R09=00000000 R10=00000000 R11=00000000

R12=00000000 R13=20010000 R14=ffffffff R15=0000002e

XPSR=61000000 -ZC- T priv-thread

FPSCR: 00000000

(qemu) x /16xw 0x20000000

20000000: 0x00000005 0x00000006 0x0000000b 0x00000000

20000010: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

20000020: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

20000030: 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000 0x00000000

The numbers and their sum are available in the SRAM beginning at 0x20000000. We now have almost everything we need for a C program to execute on our hardware. What we’re missing is changes required to identify and relocate the .bss section for uninitialized variables, identifying the vector table or interrupt vector table for the hardware and including it into the data section and a means for displaying Hello, World.

Let’s go back ot the data sheet and look at table 2-8 which lists the exception (or interrupt types) and thier vector addresses. Vector addresses refere to addresses in the memory map where the interrupt service routines are to be located. The table suggests that vector addresses begin at 0x00000000 with the last vector located at address 0x000000EC. This means that the first 0x000000F0 == 240 bytes should represent calls to interrupt service routines (handlers). With this in mind, we can construct the C-runtime or startup code for the hardware that will look like this:

.syntax unified

.thumb

.section .vectors, "x"

.word _sram_stacktop /* 00: Initial Stack Pointer */

.word _start /* 01: Initial Program Counter (Reset) */

.word _hang /* 02: Non-Maskable Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 03: Hard Fault Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 04: Memory Mgmt Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 05: Bus Fault Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 06: Usage Fault Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 07: Reserved */

.word _hang /* 08: Reserved */

.word _hang /* 09: Reserved */

.word _hang /* 10: Reserved */

.word _hang /* 11: SVCall Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 12: Debug Monitor Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 13: Reserved */

.word _hang /* 14: PendSV Interrupt */

.word _hang /* 15: SysTick Interrupt */

.text

.thumb_func

_start:

/* zero all general-purpose registers */

mov r0, #0

mov r1, #0

mov r2, #0

mov r3, #0

mov r4, #0

mov r5, #0

mov r6, #0

mov r7, #0

mov r8, #0

mov r9, #0

mov r10, #0

mov r11, #0

mov r12, #0

data_relo:

ldr r0, =_flash_sdata

ldr r1, =_sram_sdata

ldr r2, =_sram_edata

/* handle case where data section size is zero */

cmp r2, r1

beq bss_relo

data_loop:

ldrb r4, [r0], #1

strb r4, [r1], #1

cmp r2, r1

bne data_loop

bss_relo:

mov r0, #0

ldr r1, =_sram_sbss

ldr r2, =_sram_ebss

/* handle case where data section size is zero */

cmp r2, r1

beq finish

bss_loop:

strb r0, [r1], #1

cmp r2, r1

bne bss_loop

finish:

bl main

_hang:

b .

The changes here from the prevoius assembly example are:

- We now have the first 60 bytes of the program set aside for the interrupt vectors. Although this list should be 240 bytes == 60 interrupt vectors, this should do for starters. You can go ahead and put in placeholders for the remaining 45 interrupt vectors. These are marked as a sperate section called

.vectors. The attributexinidcates that it is executable - as it holds the addresses of interrupt handlers. - Just like we introduced code to relocate the data section, we have code to relocate the bss section. Following this, we call our main function.

We save this file asstartup.s.

With our startup code setting up the C runtime environment, we can now program in C. Let’s see what a simple Hello, World program looks like.

#include <stdint.h>

/* We'll be using the serial interface to print on the console (qemu)

* For this, we write to the UART.

* Refer: http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf Table 2-8

* for the mapping of UART devices (including UART0)

*/

volatile uint8_t* lm3s6965_uart0 = (uint8_t*)0x4000C000;

void serial_print(const char* msg)

{

while(*msg)

{

*lm3s6965_uart0 = *msg++;

}

}

void main(void)

{

const char *start_msg = "Hello, World";

serial_print(start_msg);

while(1);

}

We’ll be using the UART serial interface to write to the console. If you check table 2-8 in the data sheet, you’ll see that this interface is mapped to address 0x4000C000. Since this is QEMU and not real hardware, we can simply write to this address and have our data dispalyed on the console (although on real hardware, the UART will have to be configured suitable before it can be used. We’ll be dealing with this in the next chapter).

We could’ve written to serial within main, but we’ve chosen to call a function as this would exercise stack usage (saving arguments and return address, unwinding the stack on return) - which is a good way to determine if our startup code works as expected. Let’s save this file as serial_print.c.

Let’s also modify our linker script to account for the .bss section and the newly included .vectors section:

MEMORY

{

FLASH (rx) : ORIGIN = 0x00000000, LENGTH = 256K

SRAM (rw) : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 64K

}

SECTIONS

{

. = 0x00000000;

.text : {

KEEP(*(.vectors))

* (.text)

. = ALIGN(4);

} > FLASH

.data : {

_sram_sdata = .;

*(.data)

. = ALIGN(4);

_sram_edata = .;

} > SRAM AT > FLASH

_flash_sdata = LOADADDR(.data);

.bss : {

_sram_sbss = .;

*(.bss)

. = ALIGN(4);

_sram_ebss = .;

} > SRAM AT > FLASH

_sram_stacktop = ORIGIN(SRAM) + LENGTH(SRAM);

}

The .vectors section is subject to the KEEP command which instructs the linker to never eliminate the section.

The manner of building the executable is the same, except the new file serial_print.c has to be compiled and assembled without linking it - using the appropriate options. Then, when linking to generate the ELF file, use the object files startup.o and serial_print.o as inputs. Let’s build an elf called hello.elf and then generate a raw binary hello.bin from the same. Let’s then run it on QEMU:

qemu-system-arm -M lm3s6965evb -kernel hello.bin -nographic -monitor telnet:127.0.0.1:1234,server,nowait

Hello, World

So, there we have it. We’ve built a C runtime environment and used it to build/execute our first C program on a bare-metal system.

You can refer to the code in assembly here or the same in C (yes, all of it including the C runtime code written in C!) here. I’ve used makefiles to assist with building code and executing it - which I hope you’ll find useful.

In this next chapter, we’ll look at how we can program the UART/serial hardware to read/write data - as an input/output device. We’ll do this in C language, of course.

References:

There are some really great references out there that go in depth as far as the compilation/assembly/linking/loading aspects go.

The one I found quite useful and elaborate is this tutorial by Vijay Kumar particularly sections 4 to 10.

Another great resource for assembler directives, linker scripts, make etc is this. It serves well as a reference/lookup.

Like I mentioned already, whenever a question pops in your head, look it up - seek, and ye shall find.