Previously, we got our C runtime environment which allowed us to start programming in C on a bare-metal system. We went on to get Hello, World printed on the console, which was great. It would be nice to have the ability to write what we want to the console or even read from say some hardware registers and display that info on the console. All in all, communication with our system is pretty useful. Enter, the Universal Asynchcronous Receiver Transmitter UART. This peripheral can be read from/written to - and as we commented earlier, the serial port/UART is redirected to the terminal/console (just one of the many uses - you could use the UART to communicate between two systems, for instance).

UART basics

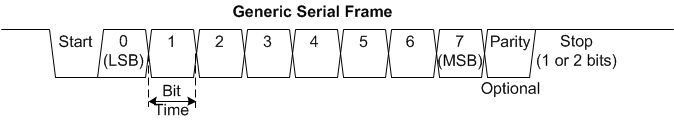

Although it is the simplest of the serial communication protocols, let’s get familiar with how it works:

UART communication involves a pair of devices sending data on one wire and recieving data on another. The communication doesn’t require the use of a clock or synchronization signal, instead the devices are configured to communicate at the same baudrate (baud referes to a unit of transmission speed equal to the number of times a signal changes state per second - which translates to bits per second in the digital communication universe. The term is originally from the world of telegraphy). The data transmitted is interpreted as packets by either side of the communication - with each packet composed of a start bit, 5-9 data bits, a parity bit and 1-2 stop bits.

The two UARTs in communication should use the same packet framing format (along with the same baudrate) to communicate successfully.

What are we dealing with?

The hardware we’re using, Stellaris LM3S6965, comes with three fully programmable 16C550-type UARTsperipherals on board. The 16C550 UART refers to an integrated circuit used for serial communication on which the said UART interfaces are modelled. These UARTS come with FIFOs for transmission/reception of data, support a baudrate of upto 3.125Mbps, support IR (infra-red) transmission/reception and so on. Section 12 in the data sheet provides details about this and more.

Controlling the UART devices is doen through what are termed special function registers (SFR) that are unique to each of the UART peripherals supported. The aspects of the UART and it’s usage contorlled by these registers include - baud rate, packet format, holding data for transmission/reception, status of the UART, error status, controls etc.

Of these, the ones that we’ll be using here are:

UARTDATA: The register that holds data to be sent/received. Although there is are 16 FIFOs each for sending and recieving data, we’ll start by using this register exclusively lfor all our communication.

UARTRSR/UARTECR: The receive status register/error clear register - records any error in communication. The registers contents can be cleared.

UARTFR: This is the flag register that records the status of the UART FIFOs and indicates wheteher UART is busy.

UARTIBRD and UARTFBRD: These registers are used to set the UART baud-rate.

UARTLCRH: This register, called the line control register is used to control parameters such as data length, parity, and stop bit selection.

UARTCTL: This is the UART control register used to enable/disable the various capabilities of the UART device.

What do we want out of the UART?

As discussed in the beginning, we want to be able to send and recieved data via the UART device. The device in communication with us will be the console represented by the standard input and standard output in the current example. Although, we’d want to write software that can operate the UART to communicate with any UART capable device - in other words we will program a device driver. The software that we write to communicate with the console using the driver APIs will be our application. So, at the end of this we’ll have harware -> hardware startup and initialization -> device driver -> application software. See how the various software layers are being formed as we move along.

Devil in the details:

In it’s most basic form, a device driver will have the following capabilities:

- Initialization: starts up the UART device.

- Configuration: configures the UART device in accordance with the agreed upon transmission rate and packet format.

- Runtime functionality: the send and recieve functionality during UART operation as well as error detection and handling during device operation.

- Termination: stop/disables/turns-off the device. This bit is usually omitted.

The source code, linker script and makefile for this section can be found here.

Now, let’s start with the initialization and configuration capabilities - and translate them into functions. The data sheet has a great follow along example if you refer to section 12.4. Notice how there are references to setting bits in the SFRs referenced earlier. How do we do this programmatically?

Take a look at table 12-3 in the data sheet that gives you the offsets of the various SFRs - from the UART base address. One way of programmatically representing this is via macros with one for the base address (representing the particular UART device) and a bunch of others forholding the offsets of individual SFRs. We can then have a pair of functions to:

- get register - returns a pointer representing an individual SFR = base address of UART + offset of desired SFR.

- put register - assign the desired value to program the desired SFR represented as a pointer = base address of UART + offset of desired SFR.

Another way, which I have chosen is to create a structure representing a UART device such that each member of the structure corresponds to an SFR. Notice how the SFRs offsets are strictly ascending - by choosing the right data type to represent each SFR - uint32_t. We use this fixed length integer type (defined in stdint.h) beacuse each register spans a full 32 bits. The layout and size of the SFRs is fixed, as described in the datasheet and the structure representing them will look like this:

typedef struct __attribute__ ((packed)){

uint32_t DR; // 0x00 UART Data Register

uint32_t RSRECR; // 0x04 UART Recieve Status/Error Clear Register

uint32_t reserved0[4]; // 0x08-0x14 reserved

uint32_t FR; // 0x18 UART Flag Register

uint32_t reserved1; // 0x1C reserved

uint32_t ILPR; // 0x20 UART IrDA Low-Power Register Register

uint32_t IBRD; // 0x24 UART Integer Baud-Rate Divisor Register

uint32_t FBRD; // 0x28 UART Fractional Baud-Rate Divisor Register

uint32_t LCRH; // 0x2C UART Line Control Register

uint32_t CTL; // 0x30 UART Control Register

}uart_regs;

Couple of things may have struck you as unusual. First, the use of __attribute__ ((packed)). The reason for this is to instruct the compiler that the structre that follows is packed and should not be padded. Why, you may ask? Because, the structure strictly represents the layout of the SFRs in the UART device in keeping with the offsets provided by the manufacturer. For instance, at offset 0x0000 from the base address lies the UARTDR and the UARTRSR\UARTECR is at offset 4. This implies that the structure member representing UARTRSR\UARTECR must follow the one representing UARTDR. Whereas, UARTFR is at an offset 0x0018 from the base address or 0x0018-0x0008 = 0x0010 from where UARTRSR\UARTECR ends. We ensure that the member representing UARTFRis at the right offset by introducing uint32_t reserved0[4] before defining it. This is why you see a couple of these reserved members in the structure - the other unusal thing you may have noticed. When you add it all up along with how structures are realised and their members are addressed, you see that this is an accurate software representation of a UART device.

Now how do I access UART0 using this structure? Simply:

volatile uart_regs *uart0 = (uart_regs*)0x4000C000u

This sets the struct variable uart0 at the base address of the UART0 device. Since the struct is defined to reflect the SFRs accurately via the members placed at the appropriate offsets, this should help us access UART0 and its SFRs.

why volatile? Because we want every operation invoving uart0 to read from and write to it’s seleted SFRs and not allow the compiler to optimize any operation away.

With this in place, let’s go back to the example in the data sheet at section 12.4. The example suggests that we set up the baud rate and the packet format for communication, disable use of FIFOs and interrupts and then turn-on(enable) the UART device for operation. The assumption here is that the UART device is turned-off before initializaton - something that we’d rather have in software than simply hanging about as an assumption. These steps can be implemented as functions that will:

- disable the UART device.

- set the UART device baud-rate as desired.

- set the line controls i.e. packet format, enable/disable FIFOs.

- enable the UART device.

Disabling the UART device involves clearing the UARTEN bit - which is the 0th bit - in UARTCTL register. We do this by:

uart0->CTL &= 0x00000000u;

Now, this very same bit can be set to enable the UART device. In order for us to be able to turn-on/turn-off the device as well as avoid using “magic” numbers, we can define the UARTEN bit as:

#define UARTCTL_UARTEN 0x00000001u

and disable the UART device like so:

uart0->CTL &= ~UARTCTL_UARTEN;

As you can see, this helps with readbility too, with the later snippet being almost self explanatory compared to the former.

But does this suffice, as far as disbaling a UART goes? What if the UART was in operation or what if the data register had something that was not sent/read yet? It is best not to make assumptions and handle these cases:

static void uart_disable(void)

{

/* clear UARTEN in UARTCTL*/

uart0->CTL &= ~UARTCTL_UARTEN;

/* Allow any ongoing transfers to finish */

while(uart0->FR & UARTFR_BUSY);

/* Flush the FIFOs by (disabling) clearing FEN */

uart0->LCRH &= ~UARTLCRH_FEN;

}

uart0->FR & UARTFR_BUSY gives us the BUSY bit in teh flag register UARTFR and UARTLCRH_FEN represents the FEN (FIFO enable) bit in UARTLCRH which we clear to flush any data in the FIFOs.

#define UARTFR_BUSY 0x00000008u

#define UARTLCRH_FEN 0x00000010u

You can have these definitions in a header file like this.

Now, we have to set the baudrate of the UART device to 115200. The UART SFRs - UARTIBRD - holds the integer baud-rate divisor while UARTFBRD - holds the fractional baud-rate divisor. The baud-rate divisor here is a 22 bit number (BRD) - with a 16-bit integer (BRDI) and 6-bit fractional part (BRDF). It is related to the baud-rate as follows:

BRD = BRDI + BRDF = UARTSysClk / (16 * Baud Rate)

BRDI = floor(BRD)

BRDF = floor((BRD-BRDI) * 64 + 0.5))

UARTSysClk refers to the frequency of the system clock connected to the UART. If you refer to Table 5-5 of the data sheet, you will find that this is set to 12.5 MHz, by default. WE will see how to tune this in a subsequent chapter, but for now, the default value will do.

BRD = 12,500,000 / (16 * 115,200) = 6.7817

BRDI == 6

BRDF == integer(0.7817 * 64 + 0.5) = 50

This can be implemented as a function:

static void uart_set_baudrate(uint32_t baudrate)

{

uint32_t brdi, brdf, dvsr, remd;

/* Refer http://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/lm3s6965.pdf 12.3.2 */

dvsr = (baudrate * 16u);

/* integer part of the baud rate */

brdi = UART_DFLT_SYSCLK/dvsr;

/* fractional part of the baudrate */

remd = UART_DFLT_SYSCLK - dvsr * brdi;

brdf = ((remd << 6u) + (dvsr >> 1))/dvsr;

uart0->IBRD = (uint16_t)(brdi & 0xffffu);

uart0->FBRD = (uint8_t)(brdf & 0x3ffu);

}

There is one more thing that needs doing to get our UART working - the peripheral clock must be enabled by setting the UART0 (since we’re using UART0 device) bits in the RCGC1 register. This is a system control SFR meant specifically for clock control - a module we’ll deal with in a later chapter. For now, let’s simply set the UART0 bit of the register, like so:

static void set_clk_uart0(void)

{

uint32_t *pRCGC1 = (uint32_t*)0x400FE104u;

*pRCGC1 |= 0x00000001u;

}

And finally, we set the packet format and disable FIFOs in the UARTLCRH register as follows:

static void uart_set_example_line_ctrls(void)

{

uart0->LCRH = UARTLCRH_EXAMPLE;

}

where, UARTLCRH_EXAMPLE has been defined to set data lenght to 8 bits, one stop-bit, no parity bits and disable FIFOs. We can set these individually by using macros for each bit in UARTLCRH. Finally, we then enable UART device via:

uart0->CTL &= ~UARTCTL_UARTEN;

Giving and receiving

Sending data is fairly simple, all we have to do is write data as a byte into the UARTDR register when the UARTDR isn’t full . The status of the UARTDR for sending data is available in the TXFF bit in the UARTFR. If the bit is set, it indicates that UART Transmit FIFO (in our case the data register) is full - hence data cannot be sent.

void uart_tx_byte(uint8_t byte)

{

/* if tx register is full, wait until it isn't */

while(uart0->FR & UARTFR_TXFF);

uart0->DR = (uint32_t)byte;

}

Recieving data, requires us to check if the received data is available in the UARTDR. This is achieved by checking if the RXFE bit - UART Receive FIFO Empty -is clear (in the UARTFR). If it is clear, then there is received data to be read in the UARTDR.

uart_err uart_rx_byte(uint8_t* byte)

{

/* if the rx register is empty, reply

* indicating that there is no data

*/

if(uart0->FR & UARTFR_RXFE)

{

return UART_NO_DATA;

}

/* Received data is 12-bits in length, with the first 4-bits

* representing the error flags and the last 8-bits, the data.

*/

*byte = uart0->DR & UARTDR_DATA_MASK;

if(uart0->RSRECR & UARTRSRECR_ERR_MASK)

{

/* the received data had an error

* write to ECR to clear the error flags

*/

uart0->RSRECR &= UARTRSRECR_ERR_MASK;

return UART_RX_ERR;

}

return UART_OK;

}

Notice how we only read the last 8-bits of the UARTDR as the recieved data. This is because the first 4-bits of the register hold error information. This error information specific to recieve data is available in the UARTRSR/UARTECR register - which we read and clear and return an error enum - to indicate recieve error.

And to put this all together, let’s stick uart_init(115200) in the main() function to set up our uart to be operational.

Now, we’ll need a way to use this UART driver to communicate with the console. The simplest thing to do is write a pair of functions to write to and read from the UART device. You can try that - maybe even write code to be able to read and write integers - who knows, even a printf and scanf implementation. If you need a starting point, take a look at this application that utilises the UART driver. As usual, modify the Makefile to include the new source files we’ve created, build the project and run the binary on QEMU. You can now see the text you sent to the uart printed on the console!

This is all we need to operate the UART.

You may have seen that we’re essentially polling to see if we have received data on the UART in uart_rx_byte by checking the RXFE bit in UARTFR. Although this works well as an example, it’s not the most efficient way to operate a UART or any device for that matter. Polling is time/resource consuming and we’ll do well to process incoming data as and when we receive it. This forms the subject of our next chapter on interrupt handling.

References:

The data sheet for the LM3S6965 serves as a great reference for UART in general and the onboard UART peripherals in particular - needless to say, always keep it handy.

To understand the UART and serial communication, there are countless resources on the internet and I guess you can find what suits you. But if you are spoilt for choice, start with the wikipedia page.

Since we did deal with quite a bit of bit manipulation and data structures - here are some resources on bitwise operations and data structure alignment.